Our Ladies

While the builder of our house museum was Andres Ximenez, women have played an integral part of the business operated within over our 220-year history. Historically women have been the silent partners of the men who built our communities, but here at the Ximenez-Fatio House Museum, the women have been the entrepreneurs and the face of their businesses. Below, learn more about the women who held their own, supported their families, and created legacies through hardships unimaginable in our modern times.

Juana Teresa Pellicer

1776 – 1802

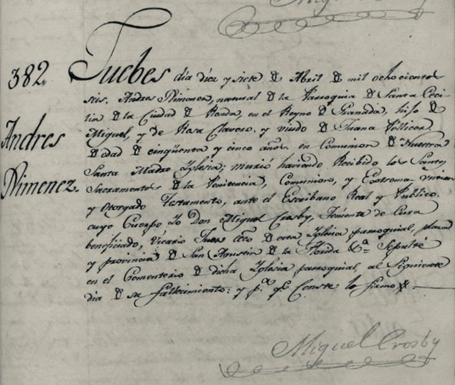

St. Augustine, April 10, 1806

Juana Pellicer was born at the New Smyrna colony of Andrew Turnbull on December 16, 1776. Her parents were Menorcan indentured servants Francisco Pellicer and Margarita Femanias. Francisco Pellicer was one of the leaders of the Menorcans who fled the colony for St. Augustine in hopes of convincing the British government of Turnbull´s abuses. After securing the freedom of the colony, Francisco Pellicer settled in St. Augustine. He continued to work as a carpenter , becoming successful enough to purchase land and move to a plantation south of the city. At the age of seven, Juana’s mother had passed away and her father remarried, having various additional children with his new wife.

In 1791, at the age of 15, Juana married Don Andrés Ximenez, 25 years her senior. They had five children. Ximenez, a native of Ronda, Spain, was a successful merchant in St. Augustine. The couple first settled on property in Hospital St. (Aviles St.), across from where our house is today. In 1797, they purchased the lot and built this house. The large coquina house had two floors, an attic, two warehouses on the western part of the property and a detached kitchen and washroom. On the first floor of the building, Andrés and Juana ran a general store and billiards hall. This local establishment, not unlike the kind found on every neighborhood in the city, served as a quick-stop of sorts for residents. After a long day fishing or working at the Castillo, one may stop at the Ximenez store for a sip of madeira, to pick up a wedge of cheese, play a round of billiards and of course, catch up on the neighborhood gossip. The family lived on the second floor.

Juana died in the house on September 6, 1802, at age 26. She was followed in death by her son Francisco, age four, and her daughter Antonia, age 13 months. Andres died in 1806, at age 56. Immediately after Andrés died, the contents of the house and store was inventoried and sold. The remaining children, which were all minors, had been living with their maternal grandfather, Francisco Pellicer, since their mother’s death.

Rents were collected for the use of the house until 1819 when, Francisco Pellicer requested from the Spanish Court to be relieved of his duties as guardian of the Ximenez children and a distribution of the estate be conducted. At that time, José was 26 years old, Miguel was 23 years old and Rosa was 21 years old.

José was married to Magdalena Peso de Burgo. Although he had been trained as a tailor, by the mid1820s he owned a ship, and had moved his family and his business to Key West. In 1825 José Ximenez sold his one-third of the interest of the house and lot to Francis Gue, a city alderman and businessman. A year later, Francis Gue sold his share of the house to Mrs.Margaret Cook. José and Magdalena died in Key West and are buried there.

Andrés and Juana´s second son Miguel, left St. Augustine to live in Santa Clara, Cuba in 1810. He was 14 years old. In Cuba, he married Andrea Vila. He was still living in Cuba in 1830 when he sold his share of the house to Margaret Cook.

Andrés and Juana’s daughter Rosa, married John Buchani in 1822 in St. Augustine. He was 32 years old and she was 24. In 1827 Rosa and her husband sold their third of the house and lot to Margaret Cook.

Margaret Rowland Brebner Cook & Eliza Whitehurst

1800 – 1829 & 1786 – 1838

Margaret Rowland was born in South Carolina in 1790. Her first husband, Archibald Brebner was a Scottish tailor. They lived in Charleston with daughter Elizabeth Margaret. After Archibald’s death, Margaret married Samuel Cook, a tailor and businessman.

Margaret and Samuel visited St. Augustine in 1812, where they began commerce operations between St. Augustine and Charleston. They made St. Augustine their permanent home in 1821, after Florida became a US territory. Besides his commerce operations, Samuel served as Postmaster and City Alderman.

The year 1826 was momentous in Mrs. Cook life. Her husband died leaving her as his heir and executrix; her daughter Elizabeth married wealthy sugar planter John Hanson; and she began purchasing the property of Andres Ximenez and Juana Pellicer from the three heirs. Mrs. Cook continued her business activities in a time when it was most unusual for a woman to know anything at all about courts and legal procedures. She bought property, owned a shop in Charlotte St., had enslaved people, and an inventory of goods valued at $2,000.00.

Mrs.Cook is credited with converting the house to a boarding house. She rearranged interior spaces in the main house, added dormers and finished the attic space. She converted the West wing facing Cadiz St. from two warehouses to rooms that could be rented. The wing and the main dwelling were unified by a galleried porch on both floors.

When the sale of the house was finalized, Mrs. Cook entrusted its operation to another widow, Eliza C. Whitehurst, who had arrived from Charleston with her daughter Anna. Recent research speculates that Mrs. Cook and Mrs. Whitehurst were sisters because of their close and intertwined multi-generational relationship. Mrs. Whitehurst son Daniel, was already living in St. Augustine as part of Mrs. Cook’s household.

The boarding house business was a success. In 1834, 22 “strangers” are listed in the local newspaper as staying in “Mrs. Whitehurst Boarding House”, as the house was known. In that same year Anna married John Hanson’s brother, James. Unfortunately, three years later, James died in a shipwreck off the coast of Savannah. Anna went to live at John Hanson’s plantation, where their daughter Mattie was born.

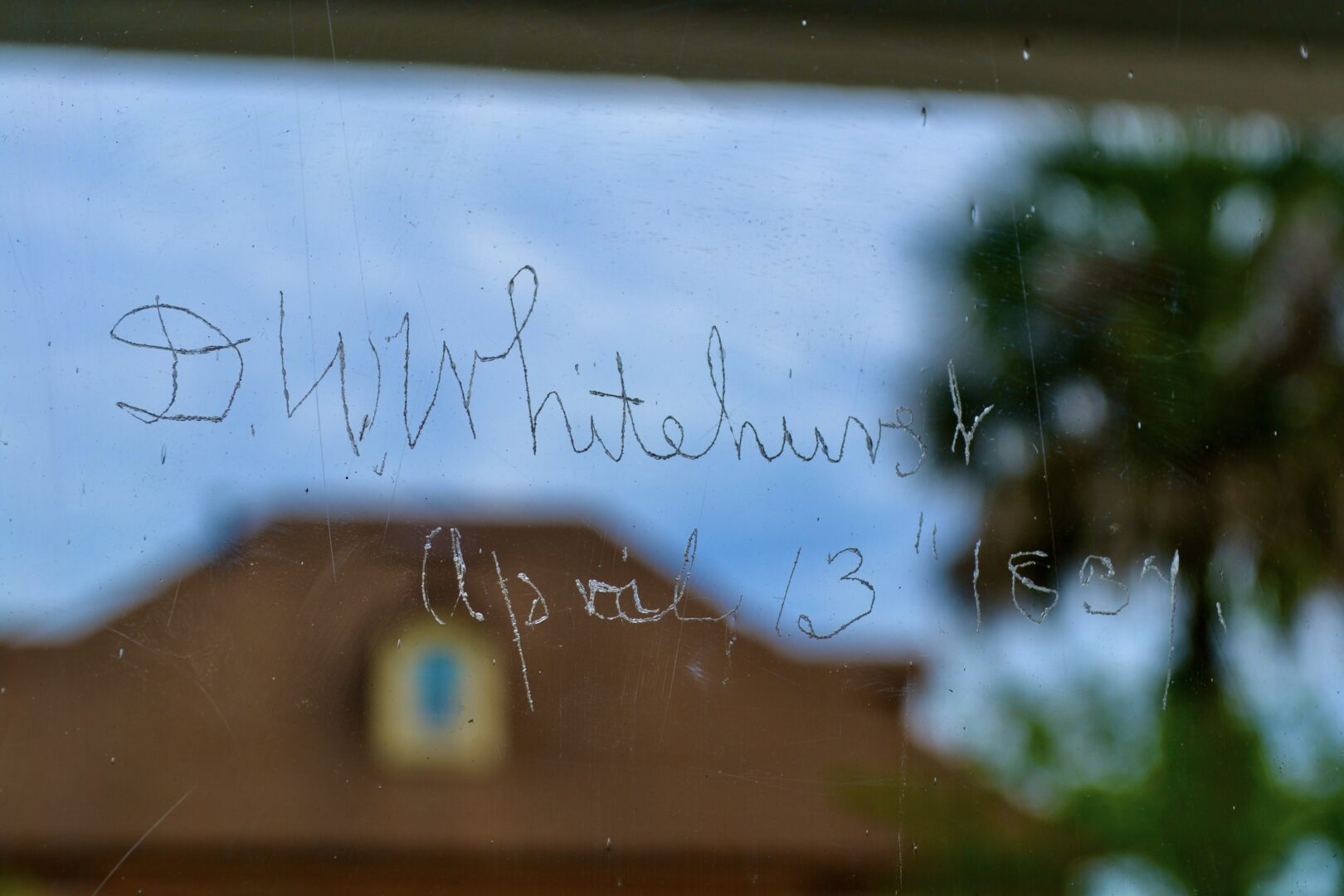

Mrs. Whitehurst’s son Daniel became prominent in St. Augustine. He served as officer during the Second Seminole War, became a newspaper publisher, was notary public, studied law and medicine. He left an etching of his signature in the owner’s parlor window closest to the pianoforte.

After a long illness Mrs. Whitehurst died in 1838. She is buried in the Huguenot Cemetery in St. Augustine. That same year, Mrs. Cook sold the house to another widow, Mrs.Sarah Petty Anderson. Mrs. Cook’s daughter died that year as well, and she moved in with her son-in-law John Hanson and their five year old daughter Margaret. She began a long business relationship with Mr. Hanson. She maintained a house on Charlotte St., while living at Hanson’s plantation. In 1873, Mrs. Cook transferred this property to Mrs. Whitehurst’s granddaughter Mattie. Mrs. Cook died sometime before 1879. Mattie continued to winter in St. Augustine, in the house left to her by Mrs. Cook, until 1899.

Sarah Petty Anderson

1782 – 1869

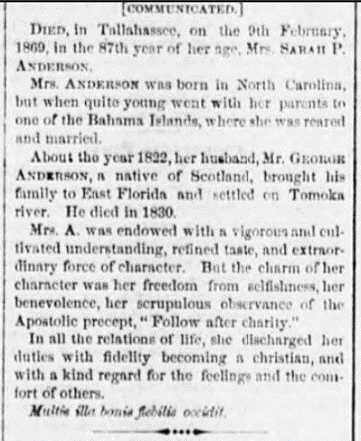

Sarah Petty Dunn Anderson was born in Salisbury, North Carolina in 1782. She was raised by her mother Frances Dunn Kerr and stepfather James Kerr in Florida and the West Indies. In 1800, she married George Anderson in the Turks and Caicos Islands, West Indies. Their children John George, James Kerr, Maria William and Jane Frances Winifred were born there. After her mother died, Mrs. Anderson received a large inheritance as well as a 450 acre plantation known as The Ferry. Along with her husband George they also owned a 1900 acre plantation known as Mount Oswald, located at the fork of the Tomoka and Halifax Rivers in today’s Volusia County. Mr. Anderson died in the 1830s. With her sons, John George and James Kerr, Mrs. Anderson bought a third plantation which she named Dunlawton. This property was burned in a skirmish called The Battle of Dunlawton during the Second Seminole War in 1836. Mrs. Anderson and her daughters escaped to St. Augustine where they lived for almost 20 years.

As a result of the Second Seminole War, St. Augustine was crowded with the rich and poor alike. Soldiers, farmers, plantation owners, traders, trappers, and free blacks – families emerged from the swamps and forests and flocked to St. Augustine in search of safety.

Because of the influx of people into St. Augustine, boarding houses were sorely needed. Those with enough business sense and money could make a nice respectable living running such houses. Mrs. Anderson purchased Mrs. Whitehurst’s Boarding house in 1838. The cheval mirror still seen today at the Ximenez-Fatio House Museum in the “owner’s bedroom” is a piece originally owned by her. She and her family lived in the house and when space was available, rented rooms to visitors. John Hammond Moore, a visitor to St. Augustine during that time describes an evening at Mrs. Anderson’s house: “The society in this place is good. Mrs. Anderson has two very agreeable daughters, Mrs. Shaw and Miss William… I spent the evening at Mrs. Anderson’s – where I had the pleasure of being made acquainted with General Hernandez.”

In 1851, Mrs.Anderson hired Miss Louisa Fatio to manage the boarding house after she decided to move to Tallahassee, FL to be closer to her family. Mrs. Anderson died in Tallahassee in 1869 and is buried in St. John’s Cemetery. Many of her descendants still live in that area.

Louisa Fatio

1797 – 1875

c. 1817, Ximenez-Fatio House Museum

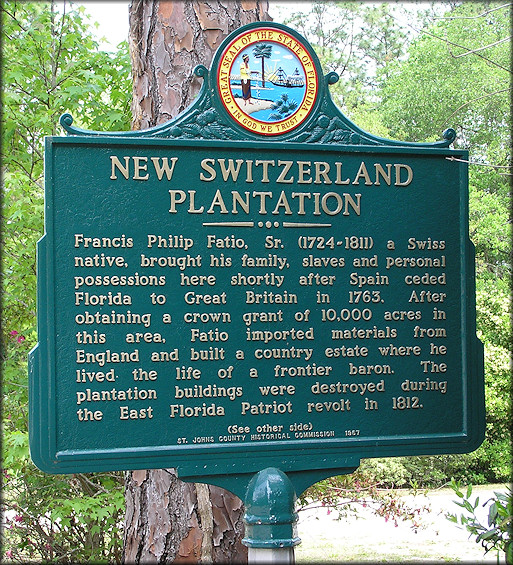

New Switzerland Plantation.

(Miss Fatio is looking out the bottom window)

Miss Louisa Fatio, a “most estimable and popular lady” as noted by a visitor to St. Augustine in 1856 was born Luisa Phelipa Patricia Fatio on March 17, 1797 in St. Augustine. She was the first child of Francis Philip Fatio Jr. and Susan Hunter. In the 1864 census, she was described as being 5’ 2” tall, with blue eyes and light complexion.Louisa’s grandfather, Viscount Francis Philip Fatio Sr., moved his family to British East Florida in 1771. He was granted vast parcels of land by the British government along the St. Johns River, northwest of St. Augustine, in the area which he named New Switzerland. By the time of his death in 1811, Fatio owned 10,000 acres of land with 12 miles of riverfront where, with the help of dozens of enslaved people, grew cash crops and produced naval supplies.

Because of their social status and wealth, Miss Fatio and her siblings were educated and taught various languages. However, the affluent Fatios were not immune to Florida’s war-torn ways. Indeed, the New Switzerland plantation house was burned down during the Patriot War of 1812. The Fatio family, which by now included 7 children (including 15 year old Louisa), abandoned the area. They endured harrowing and perilous times until ten years later, when a house was rebuilt in New Switzerland.Miss Louisa Fatio remained unmarried her entire life. Although there are rumors she had a British officer fiancé, there is no name or written evidence of this suitor. Because she was unmarried, she was expected to live with her family. However, Miss Fatio not only lived on her own — she controlled her finances and worked for a living. She also raised her sister Leonora Fatio Colt’s children with the help of sister Sophia.

By 1840, travelers started arriving to St. Augustine. Without crossing the Atlantic, Americans could enjoy the pleasures of a semi-tropical climate and, in St. Augustine, get the feel of an old Spanish town. Not all tourists visited for pleasure. During this era, pulmonary diseases were widespread throughout the nation. With little knowledge on how to treat their patients, doctors encouraged invalids to spend the winter in warmer climates. Thus, invalids began to fill boarding houses and hotels.Miss Fatio took advantage of this situation to get into the boarding house business. In 1839, she started managing a boarding house for Kingsley Beatty Gibbs, Zephaniah Kingsley’s nephew, in the Bayfront. By 1850, she had set up her own boarding house on St. George Street. A year later, she went to work at Miss Anderson’s boarding house on Hospital (today Aviles) Street. Four years later, she purchased the building and property for $3,000.00. Soon after Miss Fatio renovated the second story of the west wing of the house, adding additional rooms to rent. She renamed it Madame Fatio’s Boarding House, better known today as the Ximenez-Fatio House.

On January 1st of 1861, Florida seceded from the Union. In April the war started. Only a year later, Union forces occupied St. Augustine. For the rest of the war the town remained in Union control, while the countryside was Confederate territory. Living in a small town, neighbors tried to make life bearable for each other by sharing what they could. Regardless of which side of the war they supported, the town scraped by together.Where the Fatio household stood in this conflict is not part of the historical record and very little documentation is available on how Miss Fatio fared. Her sympathies might have been with the Confederates — just as her father and grandfather had before her, she owned people and her business benefited from slavery. However, in 1864, Miss Fatio took the Oath of Allegiance to the Union government. It is a testament to her character that she was able to hold onto her property and keep her business alive through America’s bloodiest war.

The Reconstruction period that followed was difficult as the nation recovered from the horrors of the war. By the 1870s, the tourism industry in St. Augustine was recovering fast. Records show that Miss Fatio was able to employ two servants — Louisa Williams and Lewis Williams, who were not related. These former enslaved people had been liberated in St. Augustine in 1863. In contrast to the empty streets of decades past, the city began to fill up with tourists. To secure a room in a prestigious boarding house like this one, it was important to make reservations before arrival and send ahead letters of recommendation. Most guests would arrive in mid-November and leave early May, paying between $15.00 and $20.00 per week.

“The house on Hospital Street was a large white mansion, built of coquina, with a peaked roof and overhanging balcony” is how American writer Constance Fenimore Woolson described Madame Fatio’s Boarding House during her stay here in 1873. The House and Louisa Fatio were immortalized in her story The Ancient City, which was published in Harper’s Monthly Magazine. Soon after the story’s publication in 1875, Miss Fatio died. She was seventy-eight years old. The house was inherited by the Colt children, who had lived most of their lives in the house.

The Dames

1939 – Today

After the death of Miss Fatio in 1875, the house was inherited by the Colt children, who had been raised in the house by their aunts Louisa and Sophia Fatio. The children, which by this time were already adults, continued using the house as a boarding house. Mrs. Foster became the house manager. With the newly constructed Hotel Ponce de Leon just a few blocks away with its electric lights and indoor plumbing, the boarding house lifestyle soon fell out of favor with travelers. Through the years, various businesses were operated on the first floor of the building while the rooms and even the outside kitchen were rented as living quarters for locals and visitors alike.The structure soon fell into disrepair.

In 1939, after members of The National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of Florida (NSCDA-FL) took part in successfully saving the Old City Gate, members of the NSCDA-FL set their eyes on the Old Fatio House. The structure and property were purchased in 1939 by the Dames at the height of the Great Depression. Repairs and restoration work set about immediately thereafter. For almost 10 years and beyond, weekends were spent in St. Augustine scrubbing windows, cleaning debris, restoring fireplace mantles, lime-washing walls and ceilings, researching and purchasing antiques, restoring the grand staircase, and planting historically appropriate gardens. In 1946, the Dames opened the house to the public as the Ximenez-Fatio House Museum. In the 1970s, after further restoration and research, the house re-opened as a museum interpreting the 19th century boarding house period in St. Augustine. For over 75 years the house museum has served the community as an impecable example of restoration and preservation. Today, the Ximenez-Fatio House Museum is a representation of how the house looked in the 1850s when it was known as Madame Fatio’s Boarding House. The Dames continue managing the museum as part of their mission for “ historic preservation, patriotic service and educational programs.”